By Joel K. Richards

INTRODUCTION

The current novel coronavirus (COVID-19) crisis which originated in China, and which has severely disrupted China-centric value and supply chains, has laid bare the limits of countries having outsourced their industrial policy to China. According to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), the slowdown of manufacturing in China due to the COVID-19 outbreak is disrupting world trade and could result in a USD 50 billion decrease in exports across global value chains (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development , 2020).

For most if not all Caribbean Community (CARICOM) countries, we are likely to be harder hit than any other region because we control fewer resources and stages of the supply chain. Furthermore, we are also net importers, meaning that our imports exceed our exports. For instance, in 2019, CARICOM imported over USD 31.8 billion dollars’ worth of goods whilst exporting USD 16.9 billion, representing a trade deficit of over USD 14.8 billion.

In a scenario where CARICOM countries import nearly twice as much as they export, disruptions to global supply and value chains, particularly prolonged disruptions, are likely to have devastating consequences for food and livelihood security. This places an obligation on the region to revisit the role of industrial policy in supporting its economic and social well-being. Of course, the implicit assumption here is that the region has lost ground in terms of the pursuit and execution of industrial policy measures.

The COVID-19 pandemic suggests that we are living in extraordinary times which require extraordinary imagination and reimagination. While it is important to keep one eye on the current pandemic, it is equally important to keep another eye on our preferred future. Part of this preferred future should be a commitment to emerge from the crisis better, stronger, smarter and more prosperous than we were before. In this context that a re-examination of the role of industrial policy is being proposed.

WHAT IS INDUSTRIAL POLICY?

Industrial policy is a coherent set of actions that focus on industrial transformation, with the goal of sustainable and competitive production of goods and services. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) refers to industrial policy as a process which promotes ‘high-road competitiveness’, understood as the ability of an economy to achieve ‘Beyond-GDP’ Goals. In essence, ‘high-road’ strategies are based on advanced skills, innovation, supporting institutions, environmental goals and social policy (Aiginger, 2014).

WHY INDUSTRIAL POLICY?

The most successful examples of late developers, particularly in East Asia, have all had targeted industrial policies. Productivity growth and technological advancement lie at the heart of economic development and this reality underscores the value of industrial policy to the economic fortunes of countries. Industrial policy can be a major source of technology-driven productivity growth in modern economies. For example, the world’s most productive farms use the most advanced machinery while the most industrious services utilize state-of-the-art transport equipment and computers. This suggests that an industrial policy which promotes these kinds of outcomes is important in the context of national productivity, innovation, jobs and the overall welfare of the state.

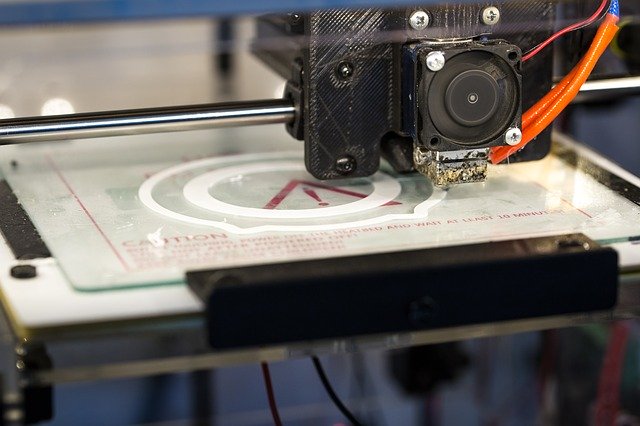

There are also several developments taking place around which a modern and progressive industrial policy should be built. Mobile Supercomputing. Intelligent Robots. 3D Printing. Many economists, political and business leaders from around the world are convinced that we are on the cusp of a new industrial revolution that is fundamentally changing the way we live and work. These developments are disrupting the traditional ways of doing business and those who fail to adapt will be left behind.

As the new industrial revolution unfolds, many more innovations are in store. Advances in computing power, artificial intelligence, robotics and material science can hasten the shift toward more environmentally friendly products of all types. Digital fabrication techniques, such as 3D printing, can bring manufacturing closer to customers. New energy technologies can create low-cost, abundant and sustainable sources of power and power storage to rid us of our over-reliance on fossil fuels. These innovations are revolutionizing manufacturing, production and business around the world and countries need an industrial policy that can be responsive to and promote advances in these areas.

A TEN-POINT PLAN FOR INDUSTRIAL POLICY

The following industrial policy blueprint is being proposed for the consideration of the CARICOM region:

- Business climate improvement in areas such as access to credit; ease of access to government services; improved inter-agency and inter-ministerial coordination; and the establishment of good regulatory practices in areas such as access to laws and regulations, and efficient mechanisms for grievances and complaints for the private sector. These measures could support increased competition and boost investor confidence.

- Exploitation of economic niches in areas such as the ocean’s economy to secure sustainable outcomes with respect to fisheries, energy, water and electricity.

- Set tax incentives to encourage investments and innovations with respect to energy efficiency and new and emerging technologies.

- Encourage a climate of cooperation between government, the private sector and the academic community on matters relating to innovation and industrial transformation.

- Develop policies and programs that promote economic and export diversification.

- Strengthen links between the agricultural and manufacturing sectors to encourage value-added food production.

- Improve connectivity by building digital infrastructure and capacities and improving the affordability of and access to world-class information technology goods and services.

- Reform the education system to be more aligned to the needs of the business community.

- Create green growth policies considering the potential of the green economy to accelerate economic transformation.

- Redefine the role of the state in the economywhereby the state transitions out of areas that are better served by private investments while acting as an incubator for areas of economic activity that remain underdeveloped with the goal of transitioning when the desired level of maturity is achieved.

CONCLUSION

The measures enunciated above are not a panacea for some CARICOM’s structural problems, but they can assist in helping the region to become more competitive, even if they do not allow it to have full control of its supply chains. They can also help to cushion the blow from exogenous shocks like what such as what COVID-19 has brought about.

Furthermore, the current COVID-19 crisis has exposed and reinforced vulnerabilities in the economies of some CARICOM countries that need to be addressed. Some of these countries remain vulnerable to disruptions in global supply and value chains partly because of the decimation of their industrial capabilities. Therefore, to build and strengthen economic and social resilience, the region should encourage policies that lead to industrial development and economic diversification. The region now has a once in a generation opportunity to re-format its social and economic models for future prosperity.

Finally, as bad as the current crisis is, it does present opportunities for thoughtful conversations about how things can be done differently, including things that should have been done already. We should not waste this moment!

DISCLAIMER: The author remains solely responsible for any errors or omissions. The views expressed are solely those of the author.

Joel K. Richards is an International Trade and Development expert from the Caribbean (MITP Graduate), based in Geneva and a contributor to the Shridath Ramphal Centre’s Trading Thoughts column. Learn more about the SRC at www.shridathramphalcentre.com